- Home

- Patrick Wright

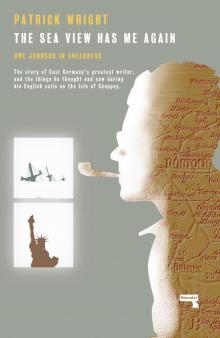

The Sea View Has Me Again

The Sea View Has Me Again Read online

“Patrick Wright has written an extraordinary, haunting book, a devastating allegory of our own time, yet seen from the mid-twentieth century. Wright’s phenomenal achievement is to painstakingly set the scene against which the final volume of Uwe Johnson’s monumental four-part novel Anniversaries can be read and to turn it back to us, with a contemporary question — are we left behind or staying behind?”

— GILLIAN DARLEY, AUTHOR OF EXCELLENT ESSEX

“A double ‘biography’ of the great but always tempestuous German writer Uwe Johnson and his ultimate home, the gritty and disreputable Isle of Sheppey. ‘Biography’ is in quotes because Wright is a saboteur of genres and his books encompass multiple worlds. I stand in awe of what he has accomplished here”.

— MIKE DAVIS, AUTHOR OF CITY OF QUARTZ

“With consummate timing, when so many are locked in a blind charge towards some bigger and better crisis, Patrick Wright has picked over the landfill of a very specific Estuary culture to devastating effect. The Sea View Has Me Again is a monumental sifting and arranging of local particulars, stitched against the savage farce of a great European novelist’s elective exile. Remorseless retrievals from bunker and cranked microfilm, enlivened by human witness, make this final panel of a notable literary triptych, following on from A Journey through Ruins (Dalston Lane) and The Village that Died for England (Tyneham), into one of the abiding memorials to a tattered angel of history”.

— IAIN SINCLAIR, AUTHOR OF DOWNRIVER

“In this masterful modernist history, Patrick Wright tells the story of an island which is England, yet much more than that. Wright’s Isle of Sheppey is a de-industrialised place, not in the North, but in the garden of England; a refuge of liberties that has three prisons; a dockyard and garrison town with a pacifist MP; an island which could be destroyed by bombs left over from the war, but which far from being stuck in the past is a model for a new post-industrial world. It is the stage for an extraordinary cast of characters, among them Napoleon Bonaparte, DH Lawrence’s mother and an Anglo-Catholic fascist parish priest; the Wright brothers’ patent agent, the nation’s first indigenous aviator and the father of the British atomic bomb; the communist leader of the engineering union, an immigrant imperialist machine-tool inventor; makers of modern furniture and foreign photographers.

At its heart is the life, work, and inspiration of extraordinary East German writer Uwe Johnson who drinks himself to death in a pub run by veterans of the Battle of the River Plate. Wright scintillatingly creates, from perfectly observed fragments from the past and flashes of a better future, a British history like no other, crafted with tools forged out of hard realities of modern European history. With its steely dissing of the tidy dichotomies and exceptionalist clichés which disfigure our sense of who we are, this is Patrick Wright’s most important book. It brings Europe to England by showing it has always been here, at a moment when too many want to believe something else.”

— DAVID EDGERTON, AUTHOR OF THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BRITISH NATION

Published by Repeater Books

An imprint of Watkins Media Ltd

Unit 11 Shepperton House

89-93 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

United Kingdom

www.repeaterbooks.com

A Repeater Books hardback original 2020

1

Distributed in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright © Patrick Wright 2020

Patrick Wright asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Excerpts from: Uwe Johnson, Inselgeschichten. © Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main 1995. All rights reserved by and controlled through Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin.

“Halb Schlaf”, aus: Thomas Brasch, Die nennen das Schrei. Gesammelte Gedichte. © Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin 2013.

Translations copyright © Damion Searls 2020

Cover design: Johnny Bull

ISBN: 9781912248605

Ebook ISBN: 9781912248759

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd

There must be room for more things than go onto a television screen.

—Uwe Johnson, “Conversation on the Novel…”, 1973

CONTENTS

PREFACE

PART I. THE WRITER WHO BECAME A REEF

1. Reading Uwe Johnson in Kent, 1970–3

2. On the Move but Nobody’s Refugee

3. The Border: The Distance: The Difference

4. Praise and Denunciation: A Pain for All Zealots

5. New York City: Beginning Anniversaries

6. Leaving Berlin

PART II. THE ISLAND: MODERNITY’S MUDBANK

7. 1974: Looking out from Bellevue Road

8. Neither St Helena nor Hong Kong

9. Shellness: A Point with Three Warnings

10. Coincidence on England’s Baltic Shore

11. Leysdown: The “On-Sea” Scenario

12. Rolls without Royce: Leysdown Aloft

13. Two Ways Down to the Sea: The Trade Union Baron and the Suffragists

PART III. THE FIVE TOWNS OF SHEERNESS: DEFINITELY NOT BERLIN, NEW YORK OR ROME

14. Moving In

15. Blue-Faced and Shivering: A Town on England’s Fatal Shore?

16. Fritz J. Raddatz’s Perambulation

17. Becoming “Sheerness-on-Sea”: The Scramble for a Second Horse

18. “Black Tuesday”: The Day the World Ended

19. First Moves on the Afterlife: The Modernist Chair Comes to Sheerness

PART IV. CULTURE: THREE ISLAND ENCOUNTERS

20. All Praise to the Sheerness Times Guardian

21. A Painter of Our Time

22. A Job for the Town Photographer

PART V. SOCIETY: “I DON’T WANT TO GET PERSONAL”

23. Becoming “Charlie”

24. Sheerness as “Moral Utopia”? (On Not Meeting Ray Pahl)

25. “It’s Your Opinion”: A Postcard for the Kent Evening Post

26. Implosion: Two Stories from the Site

PART VI. THE STORM OF MEMORY: A NEW USE FOR THE SASH WINDOWS OF NORTH KENT

27. Unjamming Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass

28. Sea Defences: From God’s Will to “Puddicombe’s Folly”

29. Beach, Sea and “The View of a Memory”

30. “What is that thing?”: The SS Richard Montgomery and the “Caprice” of Bombs

31. The Doomsday Shuffle

32. Becoming Unfathomable: The Bomb Ship as “Murky Reality”

33. Explosion: From the Richard Montgomery to the Cap Arcona

34. Triumph of the Sheerness Wall

AFTERWORD

NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FREESTANDING TEXTS AND EXTRACTS FROM UWE JOHNSON’S ISLAND STORIES

Reconnaissances

Oh! You’re a German

Diagonally Across from My Window, to the Left

A German Among the English

Welcomed into the Community

So That Charles Can Write the Right Thing Too

An Involuntary Trip

&

nbsp; A Good Idea, Charlie

One of My Friends in Sheerness

Not at All, Charlie

Welcome Back

There Sit the Guys

The Esplanade Right in Front of the House

The House to the West of this One

“Having a wonderful holiday — everything’s perfect — even the road is passable — and as hard as a rock”. From “John” to “Mrs Miller”, postcard, Valentine & Co, c. 1960

PREFACE

A sign provided by the council identifies two noteworthy graves in the Isle of Sheppey’s main cemetery. The first, at plot 83 FF, marks the last resting place of Mr Frederick Peake, who somehow managed to survive the Charge of the Light Brigade while serving with the 13th Light Dragoons during the Crimean War. Unlike so many who followed their Harrovian commander, Major General James Robert Brudenell, the 7th Earl of Cardigan, into the misdirected charge of 25 October 1854, Sergeant Peake emerged from “the Valley of Death” with no worse than a shattered arm, a pension and a job, both light and enduring, in the stores at the Admiralty dockyard at Sheerness. He was buried to the sound of rifle volleys and the “Last Post” on 27 December 1906, a local hero who had lived quietly across the fields from here, at 37 Alma Road in the part of Sheerness known as Marine Town.

To find the second stone, which nobody has ever tried to elevate with flags or bugles, the visitor who has entered the cemetery by its eastern entrance on Halfway Road must walk past the tiny Jewish graveyard on the right, and press on through many regularly spaced rows of Victorian and early-twentieth-century monuments. Although some of the older graves have sunk erratically into the ground, this municipal amenity lacks the Gothick atmosphere of the churchyard at which the German Romantic poet Jean Paul launched the idea of the Death of God into European consciousness towards the end of the “Age of Enlightenment”. Paul’s “Speech of the Dead Christ” (1796) is recounted by a dreamer who, having fallen asleep in the evening sunshine, is woken by a tolling bell to find himself in a darkened churchyard where the new atheist vision is coming horribly true. The night sky is filled with a vile grey mist. Avalanches are crashing down nearby and an earthquake sends mortifying tremors through the ground. The dreamer looks on as the graves open to release the dead, who clamber out of their coffins as so many abysmal wraiths and enter the teetering church in which the risen Christ confirms his discovery: “I went through the Worlds. I mounted into the Suns, and flew with the Galaxies through the wastes of Heaven; but there is no God! … And when I looked up to the immeasurable world for the Divine Eye, it glared on me with an empty, black, bottomless Eye-socket”.1

Over the course of his forty-nine years, the fiercely secular German writer whose ashes were put into the earth at plot 54 XD on 10 July 1984, found more in life to worry about than the catastrophic question that Jean Paul, a believer, derived from his dream: “if each soul is its own father and creator, why cannot it be its own destroyer too?” Uwe Johnson’s stone lies a few yards inside the cemetery’s tree-lined brick wall, beside fields that slope gently down towards Sheerness. Many of the more recent stones nearby are inscribed with loving messages and euphemisms about “falling asleep”. Some are also adorned with tributes from the bereaved: flowers, teddy bears and miniature footballs; favourite mugs, plastic angels and — this being February — a painted Santa Claus among the cement mementos, some of which appear to have been acquired (and why not?) from Andre Whelan’s Concrete Garden Ornaments factory at the old Bethel Chapel in Blue Town, just outside the Sheerness dockyard wall. Johnson’s stone — a large rectangular slab of granite laid flat in the ground — sits bare and silent amongst all this. It gives away less even than the formally restrained Portland stone monuments placed nearby by the Imperial War Graves Commission to mark British servicemen killed in the Second World War.

Johnson’s memorial bears only a chiselled name: UWE JOHNSON. No dates, no words of sorrow or description, neither epitaph nor tribute, no gesture towards the Enlightenment values that powered this novelist’s extraordinary writing nor to any kind of personal distinction or significance. Though it might seem to embody the judgement of another initially East German writer who described Johnson himself as a man of stone, a “statue of lost cultures”2 like the inscrutable stone monoliths on Easter Island, this is also the memorial of a man who wanted, by the end of his short life, to disappear into letters. It offers nothing to the visitor who may be wondering why this great German author, whose perpetually reimagined homeland was in Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania on the East German Baltic and whose last and most important novel is set in New York City, ever came to be living in an obscure town beside the Thames Estuary on Kent’s northern shore. Nor does it offer any clue as to why Johnson’s admirers in Germany may shrink from the thought of the low-lying and marshy island on which their author chose to beach himself, his wife and their young daughter towards the end of 1974: a place more desolate, it has repeatedly been alleged, than anything encountered by Robinson Crusoe among the cannibals of the South Pacific. On the Isle of Sheppey itself, meanwhile, information about Johnson’s Kentish decade has been scarce. The council struggled even to locate his grave when, in 2005, a party from the John Brinckman Gymnasium in the no-longer East German town of Güstrow in Mecklenburg announced their intention of turning up to look for traces of their school’s illustrious former student.

Johnson had demanded the barest of funerals in his will — “I REQUEST that there shall be no music speeches flowers or any religious or other service whatsoever”.3 Though obediently mute and unyielding by comparison with its neighbours, his stone does nevertheless sometimes catch the visitor by surprise. Under dry conditions it can appear inert and dull, its well-cut lettering largely buried under dust. On winter days that are both windless and wet, the perfectly levelled stone gathers a film of rainwater, which in turn captures the branches of the alders overhead and pulls them down to float as black reflections in a sea of extravagant pink. It’s an unexpected transformation — and a secret Kentish tribute to Johnson’s own description, written on the Isle of Sheppey, of looking down at the street one wet and stormy day on New York’s Upper West Side: “Now it’s quiet, the asphalt mirror of Riverside Drive shows us the treetops in their close friendship with the sky”.4

Perhaps that arresting burst of colour, which can be bright enough to subdue the Christmas ribbons on adjacent graves, may be allowed to stand as an appropriate introduction to this famously reserved writer who nevertheless kept an eye open for utopian moments in which the promise of everyday experience might be revealed. It also reminds us that Johnson, who carried some of the heaviest burdens and responsibilities of the twentieth century through his work, nevertheless once described himself as an “unacknowledged humorist”.5 His neighbour in Sheerness, the artist Martin Aynscomb-Harris, was among those who didn’t always get the German writer’s jokes. In the end, however, he did provide a local reporter with some English words that might now be remembered before that mute stone: “He was a kind man often misunderstood because of his abrupt manner. He had no time for idle conversation or banalities. He sparred with words. He was a verbal heavyweight — an intellectual whose politics were very much to the left”.6 If we are still reaching for more, we might add a line by another short-lived German-language writer with a gift for imagining impossible islands. In a late work entitled “Bohemia Lies by the Sea”, the Austrian poet Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973) writes, “I want nothing more for myself. I want to go under”.7

In German literary circles, where the merest mention of “Sheerness” can still raise a shudder, Johnson is counted among the “casualties” of his generation — a defiantly independent writer who, like his friend Ingeborg Bachmann, appears to have laid waste to his own life.8 If there was nothing more here than a story of personal disaster brought down on a household whose surviving members have since asserted their right to privacy, there would be no case for going further. That, however, is not the situation.

By th

e time of his early death, Uwe Johnson had lived in Sheerness for more than nine years. He had moved there primarily to get away from West Berlin, and to find a place where he could complete the keenly awaited fourth and final volume of a novel entitled Anniversaries: From a Year in the Life of Gesine Cresspahl (Jahrestage: Aus dem Leben von Gesine Cresspahl), which is rightly counted among the truly major works of modern European literature. Once on the island, however, he also developed a guarded interest in the life of those around him — so much so that, by February 1979, he would announce to a seminar in Frankfurt that he “had an eye”9 towards writing a series of stories set in the county of Kent. No such volume was ever completed, although a book entitled Island Stories (Inselgeschichten) was assembled by the first director of the Uwe Johnson Society in Frankfurt and published under Johnson’s name in 1995. Eberhard Fahlke’s posthumous anthology of stories, essays and extracts from letters to friends such as Hannah Arendt and Christa Wolf gives a vivid sense of what Johnson liked, or found interesting as well as exasperating, about the economically challenged English town that sat on a remote and muddy island and bravely insisted, even in the depths of winter, on wearing the optimistic name of “Sheerness-on-Sea”. Though vivid and revealing, these fragmentary “Island Stories” — some of which are included here in English versions prepared by the American translator Damion Searls — exhaust neither their material nor the perspectives they employ.

Rather than simply trying to tell “the story” of Johnson’s English years, I have written this book with broader aims in mind. I have set out to establish who Johnson was and to suggest why both his writing and his characteristic approach to reality should matter to English-speaking readers now. I have also used his reports and despatches to guide my own exploration of the Isle of Sheppey as the gouged, disdained but by no means just distressed English “backwater” in which Johnson once claimed — and this surely wasn’t only one of his unacknowledged jokes — to have discovered a “moral utopia”.10

The Sea View Has Me Again

The Sea View Has Me Again